About a year ago, while walking into the surf, I saw a large three-foot wide, wedge-shaped shadow on the sandy bottom. At first I thought it was just that—a shadow—but then when it slowly undulated its body, churning up the sand on the bottom, and swam away, I realized it was something else.

This was an eagle ray.

Most of us have heard of stingrays, the most famed member of the ray family, and we may have heard that a ray was responsible for the death of Steve Irwin (“The Crocodile Hunter”) in Australia in 2006. However, there are actually more than 600 different species of rays, and the related skates, in the oceans, and more than twenty different species of them live in the waters around New Zealand. A number of these are endemic, that is, found only in the waters of New Zealand.

What are rays?

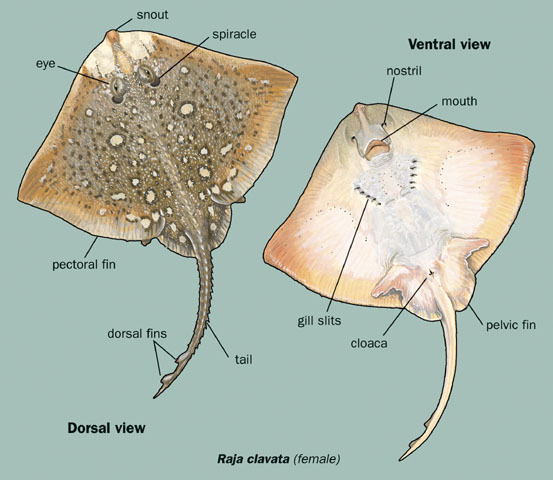

Fish can be divided into two main groups based on their skeletons: those that have true bony skeletons and those that have cartilaginous skeletons. The latter group, those with skeletons consisting only of cartilage (class Chondrichthyes), are markedly fewer in number when you look at the total number of fish in the oceans, and include both sharks, skates, and rays. Another difference is that bony fish also have what’s called an operculum, a flap of tissue that cover its gills, whereas cartilaginous fish (sharks, skates and rays) have 5-7 open gill slits on each side of their bodies—those five nasty-looking slits on the side of Jaws you see as it swims past.

In contrast with sharks, the bodies of rays and skates are flat in shape, and rather than swimming freely around the ocean, skates and rays live on or near the ocean bottom. They swim by undulating their bodies or flapping their pectoral wings. The main difference between a ray and a skate, which both look similar, is that rays bear live young (the eggs hatch inside the female), while skates lay, or rather release, eggs.

Rays vary in size. The largest rays are species of the manta ray, which can be up to seven meters (23 feet) in width. Most rays are considerably smaller. Rays are carnivores, eating fish or a variety of crustaceans. Most lay on or near the water’s bottom (the manta ray is the exception). They are often well-camouflaged, and will often flap the sand or burrow under it slightly so they can be difficult to detect.

The New Zealand eagle ray (Myliobatis tenuicaudatus), with which I began this story, is particularly common around the North Island of New Zealand in the summer. Its name derives from the fact that it supposedly has an eagle-shaped head when viewed from the side, although I think it looks more like a frog’s head. Eagle rays grow up to two meters in size and are olive-green or yellow-brown in color. They propel themselves by flapping their fins like wings, and often shoots jets of water from their gill slits to expose buried shellfish. They also have a long whip-like tail that is at least as long as their bodies.

When I saw my first eagle ray—I’ve seen more since then—how did I know it was an eagle ray, and not perhaps, one of the more dangerous varieties of stingray. Did I see its eagle-shaped head, and make my determination based on that? No, it wasn’t that complicated. A local Maori standing nearby said, “That’s an eagle ray.”

Another notable New Zealand ray is the electric ray, also called the New Zealand torpedo. These fish have two glands on either side of their heads that produce an electric charge. They feed at night and stun fish with an electric shock, and then envelope the prey with their wings. Supposedly, the charge is powerful enough to knock down an adult person.

But perhaps the most well-known ray in the world is the stingray, of which there are two varieties in New Zealand waters: the short-tail stingray and the longtail stingray. How do you tell these two apart? The short-tail stingray’s tail is the same length or shorter than its body. The tail of the longtail stingray is twice as long as its body.

While all rays have tails with which they can strike, stingrays’ tails contain a particularly nasty serrated spine which can slice deep into prey, along with venom glands that release three different types of toxins.

While the toxins are not powerful enough to kill a person, a stingray strike, due to these toxins, can be incredibly painful and the area can become necrotic (tissue can die) and infected if not treated.

Common wisdom in shallow water is to shuffle your feet along the bottom as you move forward. This serves to scare away any lurking rays, which although not aggressive, if stepped on, will often strike with their tails.

Treatment for a stingray, or any other ray, strike consists of immersing the extremity—usually it’s a foot—in hot water. This denatures (inactivates) some of the toxins, reduces pain, and helps prevent tissue necrosis. Making sure your tetanus shot is up to date is important, and antibiotics are often prescribed to prevent infection. Sometimes a piece of the spine from the ray’s tail breaks off in the wound and has to be surgically removed.

In the case of Steve Irwin, mentioned above, he apparently approached a large Australian bull ray, weighing some 220 lbs. One explanation is that the ray felt cornered by Irwin and his cameraman and reacted defensively. In any case, the ray stung Irwin numerous times with its tail, one of the stings penetrating Irwin’s heart and killing him.

A few weeks ago when my son and I rented kayaks in Ohiwa harbor near Ohope, the owner pointed out an area where we were likely to see lots of stingrays beneath the surface in the shallow water along shore. He said some of them were quite large and would flap violently splashing water if they were startled. The owner actually put a big “S” on the small map he gave us to mark the spot. But unfortunately—or maybe fortunately—we didn’t see any that day.

References:

Internet

Cox, G. and Francis M. (1997) Sharks and Rays of New Zealand. Christchurch, New Zealand: Canterbury University Press.

Klimley, A. (2014). The Biology of Sharks and Rays. Chicago, Iliinois: The University of Chicago Press.

Photo credits:

1)Summer Series 5: Is it a fish, is it a bird? …It’s an eagle ray …

www.niwa.co.nz827 × 552Search by image

2)ADW: Raja clavata: INFORMATION

animaldiversity.org553 × 480Search by image

3)f021001: Eagle ray lightly burrowed under th loose sand, as it forages.

4)An eagle ray hovering above the seafloor, showing its distinctive frog-like head and curved pectoral fins. Credit: Malcolm Francis

5)iNaturalist.org · New Zealand Torpedo observed by nzwide on May 2 …

www.inaturalist.org500 × 375Search by image

6)http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/photograph/5349/long-tail-stingray

7)FLMNH Ichthyology Department: Short-tail Stingray

www.flmnh.ufl.edu450 × 273Search by image

8)Ouch! Doctor Removes Giant Stingray Barb Stuck in Man’s Foot

www.elitereaders.com3000 × 2250Search by image

I am just getting caught up on my reading sine Thanksgiving…..I thought I’d read this one first….fish aren’t a big interest of mine…. SUPRISE … it really was interesting !!!

I’m getting educated about the ocean, in spite of myself !